ISSUE NO.10

The border is burning. As our bodies inherit the logics of ownership that underpin the age of securitisation, Joe asks what happens when self-immolation exposes the muscle of the system. Consider this the gloves, the hand in the fire.

PRELUDE

December 18th 2025

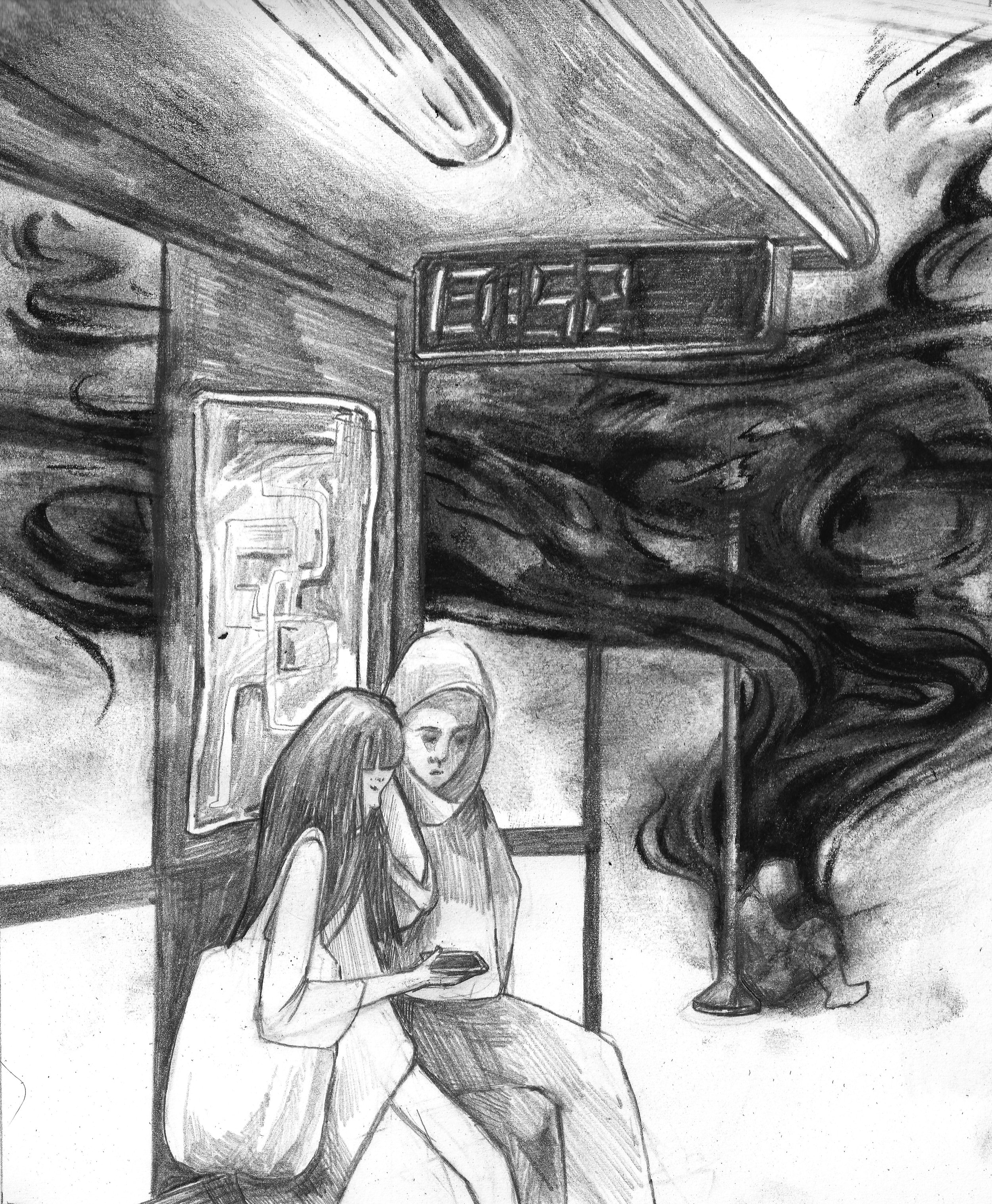

Artwork by Emily Davies

Skin

We only have open access to around 8% of land in the UK. Land across the world has been undergoing a complex process of divide, sell, own, and rule for almost a thousand years.

There are no places on earth which are not within a national border. The border is becoming more violent and repellant all the time.

Similarly, the discipline in what Erving Goffman calls “Total Institutions” is rising with our rightward tide. Prisons, asylums, schools, retirement homes- institutions whose purpose is to restrict the movement and interaction between those inside and outside, to make themselves imporous. Underfunding exasperates preexisting power dynamics- less sophisticated, more direct forms of discipline and punishment arise. Schools exclude kids at vastly higher rates. More reports of abuse in care homes. Prisons overfill and degenerate. Asylum seekers are boxed into hotels by mobs. These institutions have their own myth surrounding them. If these people are separate from us, they are no longer our responsibility, and we no longer have any need to fear them- more still, we have no more need to fear ourselves, for we are not them, and they are not us. The proof of this is in bricks, mortar and chicken wire.

These bounding forces create an elaborate network of taboos, segregations, which move through us as we move through them. Everything is carefully restricted, sealed, and given the veneer of impermeability.

How does our skin begin to look, as this way of organising the world becomes evermore hegemonic? Are the logics that govern our world not internalised and reflected in how we see our bodies? Are our bodies nation-states, total institutions, private property? And whose? Skin too becomes something like a parameter, a fence, a separation.

This is a piece about self-immolation. Watching a person set themselves on fire makes you feel physically sick. It is a visceral empathy with pain and a reaction to gore. Or we feel numb, locked off, protected from, inside ourselves, whilst that happens outside. The eyes are windows. The mouth is a door. We switch off the lights and pretend we’re not home. In liberal transformations of the idea of the self since enlightenment, we have gone from being property of God and the feudal lord to property of ourselves- but still property, to be pawned off and extracted from, split.

The contemporary spectacle of the phone-captured human being, transmogrifying within the fire, in an urban environment, runs counterwise to everything around it, and all the logics of existence it implies. The architecture around them is so explicitly invulnerable, monumental slabs of alienation, keycards, fobs, pin numbers, contactless, thumbprints, hot flesh on gorilla glass.

When a person is on fire, there is no inside and outside; a person is completely transformed into ash, carbonised. They are also transformed into a symbol. And what does that mean for my body?

With a cut, you know it shouldn’t be there. All around it, skin is how skin should be. Skin is the boundary, the cut is the place where the boundary is violated. The exception that proves the rule, a breach in the perimeter, a hole in the fence, a small boat arriving on a beach. When the entire skin is on fire, however, it breaks down entirely. The wound is more or less everywhere. The skin ceases to exist. The body on fire is an entire breaking down of many things, but for this piece the most important aspect is the breakdown of the taught relationship of discipline between the internal and external, as it physically manifests.

In December 2023, a woman sits in front of the Israeli consulate in Atlanta and sets herself on fire. When trying to define what this ‘Jane Doe’ did, the police called it arson. In calling it arson, the body is understood as private property. When Aaron Bushnell set himself on fire a few months later, they pointed a gun at him; this is how they’ve been trained, to point a gun at the threats at the opening of this border of Israel, this real estate. In America, you only set your property on fire for an insurance claim.

Suicide

But is it suicide? If it is, it can be delegitimised. It wasn’t a protest; they were mad, manic, depressed. This is often the tactic of the targets of self-immolation; states, companies, oppressors and their media arms.

As a result, the reaction to a self-immolation is often to rile against these claims, and create the perfect martyr. Clear headed, focused, single-minded, healthy, well, a life that wouldn’t have been taken otherwise. This is the idea of the perfect martyr, and of the perfect distinction between suicide and self-immolation. This too is unwise.

Depression, mania, suicidal thoughts- these are not apolitical, asocial positions of mere physical health.

In 2017, Omar Masoumali, an Iranian refugee, set himself alight in front of UN observers on Nauru, where Australia detains many of its refugees. Australia deprived him of good treatment or painkillers. As a result, he died from his injuries two days later.

This was a man who had been resisting for three years the brutal rites of passage of the Australian border for the global majority, tossed around bureaucracies and pushed, continually. Fifty more detained refugees on Nauru attempted self-immolation or suicide in the following months. A child walked into the sea. Self-harm is often a desperate means of asserting and creating bodily sovereignty in response to the continued violations of other powers.

Desperation is the active form of despair. Etymologically it means despair made active. Despair is a form of hopelessness; it is the feeling that there is nothing to look towards, that there is nothing to see, nowhere to go. Desperation animates that feeling, directs it, it is a visceral, bodily kind of mad hope. It emerges from the feeling that some radical response is needed, something almost beyond the human imagination, and beyond any capacity of organised resistance in their contemporary moment. Desperation builds a rich internal life of intense, often violent imagination. When this imaginative force of desperation is shared, organised, and educated, it can become cohesive, and revolutionary. But when these processes of sharing, organising, and education are suppressed, sabotaged, poorly mismanaged, rotting from within, that desperation does not disappear. It becomes individualised, segmented, and creates the circumstances for individualistic acts of extreme violence. Self-Immolation is one way this can manifest.

The spinning between desperation and despair is a motion many of us are going through in our political, personal lives, particularly the young. Food supply chains are threatened worldwide. At least three different genocides to our contemporary moment ongoing. No sense of anything having any power to stop the tide; I too am desperate!

People self-immolate not to die, as Thich Nhat Hanh puts it in his letter to Martin Luther King Jr., but to burn, to become a symbol, a metonym, to epitomise and speak their struggle in a language beyond language, that fire language that came about whilst our contemporary texts were still a collection of glottal grunts and moans. This is the primary difference between suicide and self-immolation. But suicide, too, has a protest element; it says that this (whatever that may be) cannot continue, and it is subsequently discontinued. Well, perhaps self-immolation is different because it attempts to send a message. But who has not felt suicide as a message, even if that wasn’t its intention? And isn’t self-immolation’s proximity to death at least a factor in its power, a power which anything in proximity to death has? Wasn’t Bushnell burning in front of a pointed gun so powerful not only in its irony, but in how it rendered the gun entirely useless, trumped it- for what use is a gun against a man who is already dead, for whom death is but a tool towards a message?

Masoumali had asked for psychiatric help before his self-immolation. Does this mean it was a suicide? And does that then mean he can be scratched from the list of historic self-immolations as protest? Can his death be delegitimised as an act of dying for a cause, just because he was unwell? When the conditions that made him unwell were precisely the things he was protesting? This issue is not by any means limited to Masoumali.

This then turns to the problem of how to write, report upon, represent self-immolation.

Writing

Self-immolation has power as an act because of its threat to life, the pain and sacrifice involved, but also the complete distortion of accepted notions of what it means to be a person, the violent unbounding, the proximity to suicide.

How do we write this? Well; no writer wants a self-immolation on their conscience. And it’s true, when one person does it, and it’s widely publicised, often others follow. When, in 1990, a man in India set himself on fire to protest government jobs being reserved for people from lower castes, two hundred followed. Biggs (2005) writes that “the World Health Organization in 1993 recommended ‘toning down press reports’” of self-immolation, for fear of copycat strikes. It is important to say that you are better off to any movement alive and well, that there are many ways to sacrifice yourself for a cause that, rather than hurting you, hurts them. The burning of the 4th precinct in Minneapolis, in the wake of George Floyd’s assassination by the police, is an example of this; and achieves a remarkably similar if not more spectacular effect. Sacrifice also doesn’t have to be a violent spectacle; it is the subtle and unglamorous work on the frontlines that truly gives any movement its roots and its power.

But our fear of the act and how to speak about it have neutered our attempts to respond to these martyrs- and that they are. Atlanta’s Jane Doe disappeared from the news cycle as soon as she arrived. Some coverage by local news outlets, some national coverage, awkwardly touching on the subject, and then silence. We don’t know where she is; it is implied she is alive, but we don’t know where, in what condition, we don’t know her name; the police deigned to mention she had a Qu’ran in her room, and had wrapped herself in a Palestinian flag, but nothing much more than that. Because she, unlike Bushnell, hadn’t emailed journalists, didn’t livestream herself, wasn’t photographed (like Thích Quang Duc). This made it easy for her to be ignored, barring a few (incredible) independent journalists working on her case. I believe she was let down by the movement around her, which, in its awkward silence, failed to advocate for her.

There has to be a way to give credence and proper respect to the act, the sacrifice, what it says in completely sublimating your will to a cause, without glorifying (which only takes away from the act, fetishising it), demonising (which is so much of the response) or encouraging. Many institutions, during the enlightenment and its inheritor, secularization, cut at least some of their ties with faith in order to survive. Marriage, the right to rule, and self-immolation being some examples.

It’s hard to talk about self-immolation without talking about Thích Quang Duc, not because he’s a famous example on a Rage Against The Machine CD, but because he marks the change from self-immolation being rooted in spiritual and religious intentions to a secular act. He was not self-immolating, as some fringe Buddhist movements had in the past, for spiritual purposes- it was not in conversation with the divine, but with the Catholic government, which was oppressing the Buddhist majority.

It was hard for secular society to understand this, particularly in the west. The state has a stranglehold on the monopoly on legitimate violence. To take the previous argument in “skin” a step further, it’s not just that we see our skin as a border and the farthest extent of our bodies, but also the furthest extent of our influence, that which we can truly revolutionise and change. Sure, we can peacefully protest, write to our MPs; we have freedom of speech, we can debate our way into influence and change, perhaps. But once that becomes anything truly disruptive, once that truly affects something, this is criminalised (see the PCSC act, Palestine Action, the shrinking right to strike, even the abolition of juries). This movement to criminalise protest that affects anything to any significant extent is underpinned by liberal, individualist notions of power; that your power begins and ends with you, that you exert no true influence over anything else beyond an evermore emaciated idea of the right to persuade, the dead horse of “speaking truth to power”.

Self-immolation throws this logic into a headspin by taking it to its extreme. If all I can have legitimate power over is myself, if the only legitimate right to affect change that I have at my disposal is over my own body, then I will set it alight. One sees the images of genocide every day, or the headlines about climate catastrophe, or is subjected to border violence for many years, or corruption, and feels one cannot take it any more- yet any route to protest in a way which could genuinely make an impact on your situation appears futile or repressed to the point of nonexistance. This repression, this shrinking of an individual’s power to themselves alone, can do what it will, but desperation is a power unlike any other; it will find a way to speak, to escape the body.

Self-immolation, by all the rules, fits the liberal, individualistic notion of legitimate protest. Most self-immolations hurt nobody beyond the person on fire, occasionally burning someone intervening. It is not a suicide bombing, for instance. It is an act of persuasion, a spoken thing, an argument, a performance. It is too great a sacrifice for a cause, in the secular world where the individual, not religion or state or cause, is supposed to be the centerpiece. The light is too bright, it dazes.

This is why I approached self-immolation from a poetic angle. It is the secular world’s best answer to prayer, to religious text- indeed it finds its origins at least in part in the verse form of scripture. It can contain contradictions (self-immolation is a cataclysm of contradictions) in a way a prose piece can’t. But we cannot simply all start writing poems when someone self-immolates. There must be an intervention in the way we respond to self-immolation.

When it comes to understanding violence and martyrdom, sacrifice and the body, we should look at how self-immolators were received in Vietnam, or Palestine, when burning in US cities to protest imperial, colonial wars. I know that they are closer to understanding violence as a banal fact of life than we are, and as such, I believe more in their response than that of our media class. A street in Jericho is named after Aaron Bushnell; his name is held up high, with no caveats, no exhausting disclaimers, no awkward shuffling around the fact. This said, a burning consulate, precinct, the furnace of a bread oven; these are more valuable to any movement than a burning body.

Illustration by Emily Davies

Joseph Conway is the Political Editor at The Lemming, based in Manchester. He is a journalist, actor, and Producer at Manchester Theatre for Palestine whilst hosting the monthly event Other People's Poetry at SeeSaw.